(English Only) (Newspaper Headline and Adverts not included)

Published: 5/1/1910

Transcript:

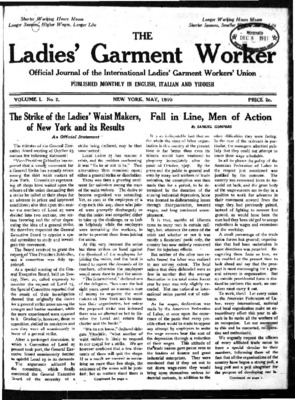

The Strike of the Ladies’ Waist Makers, of New York and its Results.

The minutes of the General Executive Board meeting of October 23 contain the following statement: “Vice-President Schindler has reported that a strong movement for a General Strike has recently arisen among the shirt waist makers of New York. Committees representing 28 shops have waited upon the officers of the union demanding that a strike be called at their shops for an advance in prices and improved conditions; also, that upon this matter the members of Local 25 were divided into two sections, one section favoring and the other deprecating the idea of a general strike. He therefore requested the General Executive Board to appoint a special committee to study and investigate this movement. The Board resolved to grant the requests of Vice-President Schindler, and a committee was duly appointed. At a special meeting of the General Executive Board, held on Sunday, Nov. 21, called expressly to consider the request of Local 25, the Special Committee reported that the result of their investigation showed that originally the desire for a general strike arose among the younger and hastier members, while the more experienced were opposed to it. Gradually, however, those in opposition yielded to conviction and now they were all unanimously in favor of a general strike. After a prolonged discussion, in which a Committee of Local 25 present took part, the General Executive Board unanimously decided to uphold Local 25 in its demands. The arguments adduced by the committee, which finally convinced the General Executive Board of the necessity of a strike being declared, may be thus summarized: Local Union 25 had reached a crisis, and the problem confronting it was “To be or not to be.” Two alternatives then remained open; either a general strike or dissolution. There was then a growing sentiment for unionism among the mass of the waist makers. The desire to become organized was extending. Yet, as soon as the employees of a shop took this step, those who joined were promptly discharged; so that the union was compelled either to take up the challenge, or to look on helplessly while the employers were terrorizing the workers, in order to prevent them from-joining the union. At this very moment the union has three strikes on hand against the dismissal of the employees for joining the union, and the local is bound to support the demands of its members, otherwise the employees would never dare to join the union. “The International,” declared one of the delegates, “has since the last eight years spent an enormous sum of money to organize the waist makers of New York and to maintain their organization, but unless the proposed strike was endorsed there was no alternative but to dissolve the Local and return the charter and the books.” “We do not know,” declared delegate Vitoshkin, “what number of waist makers is likely to respond, to our appeal for a strike. We are however confident that a few thousands of them will quit the shops. If as a result we succeed in unionizing no more than five shops, the existence of the union will be justified; but as matters stand there is no prospect of winning the strikes against the three shops. Rather than retreat from the battlefield like cowards and leave the bosses masters of the situation, we might at least involve them in a fight, the memory of which should remain with them for years. “And so the strike was declared on November 22, 1909. Not all the shops joined the strike forthwith. A number of dress and silk waist shops, particularly those where American and Italian girls were employed, remained at work. But the number of strikers far exceeded the most sanguine expectations. The employees of some of the shops immediately returned to work, because the staff of organizers was inadequate to cope with the difficulties presented by a strike of such vast extent. In most cases these subsequently re-entered the fighting lines, unable to resist their impulse to join their comrades in the front. The majority however, proved their loyalty throughout until victory was finally” won. Here the fact was demonstrated again that women are better warriors than men. They have shown exemplary loyalty, devotion and self-sacrifice. Neither the police, nor the hooligan hirelings of the bosses nor the biting frost and chilling snow of December and January damped their willingness to picket the shops from early morn till late at night. So that the lack of organizers was more than compensated for by their rare enthusiasm, dogged perseverance and noble self-sacrifice. It is difficult to give a precise estimate of the number of strikers, but there certainly could not have been less than 20,000. The confusion prevailing in the early stages of the strike is thus easily explained. It is indeed surprising that under the circumstances such splendid results were achieved. The services rendered by the Women’s Trade Union League were invaluable. Between twenty and thirty volunteers have daily performed such clerical duties as could never have been performed by the strikers themselves. Similarly, the officers of the various Jewish unions downtown, the United Hebrew Trades, a large number of the members of the S.P. and a Special Committee of the Central Federated Union have cooperated in that noble work and contributed their share to the success of the strike. During that period, November 22, 1909—February 15, 1910, when the general strike was officially called off, altogether 339 employers settled with the union”, including 19 employers with whom a compromise was effected on the basis of the open shop. Their “scabs” were retained, but 11 of these shops have since become strictly union shops. A few weeks after the strike the members of the union refused to work side by side with the “scabs;’ so that the employers were compelled to send them away and sign an agreement, conceding all the union demands. Since then 39 additional shops, the employees of which took no part in the strike have been unionized. Their employers were compelled to recognize the union and sign agreements, because members of the union refused to work there, and the employers required their services. This goes to prove that where any trade is effectively organized the employers must recognize the union and concede its demands even without a strike. What are the results, the net gain of the strike? Well, here is the answer: On an average the hours have been shortened by five per week, equivalent to $1 in wages. Price have been increased from 5 to 30 per cent., an average of 20 per cent. True, in those shops where wages were good, the raise has been comparatively smaller, while in others there has been no raise at all. That is however the proper course which a union must pursue in such cases: to equalize as far as possible the earnings. Where a union is strong there the opportunities for work and the earnings arc more or less equal and there are no “good” or “bad” shops. Another equally valuable gain is the consideration now shown to the employees, as compared with the past. Their self-respect, their independence, the absence of fear of any menial, be he foreman, designer, superintendent or shipping clerk is an inestimable blessing Every girl employed in these waist shops, feels instinctively that she is not to be slighted or trifled with by the firm, and that there is a power outside ready to take her part. As soon as the strike was over the Executive Board has taken into consideration the difficult problem of consolidating this vast mass into a ‘ well organized and disciplined body, to provide for the members meeting together and exercising their right to voice their views on all questions of management and leadership. Many projects were submitted and discussed. At first it was thought proper to group the members into sub-locals, according to their particular section of trade; as tuckers, body makers, sleeve makers, etc. But on further consideration this was shown to be inadvisable. Our experience with the cutters has taught us that this kind of grouping breeds a certain antagonism and hostility between the various sections; each of these working exclusively for its own interest. The plan finally adopted was to group all the members into seven districts and every district into two divisions. Every district contains from 40 to 50 shops and is served by one organizer or business agent. The reason for the two divisions is because the membership is much too large for one meeting. Every division meets once in two weeks. The union employees a secretary, a bookkeeper, two typewriters, one general and one assistant organizer, seven Jewish and two Italian business agents. The districts are divided as follows: District No. 1 contains all shops situated between 12th street and Harlem; District No. 2, all shops of Brooklyn and Brownsville: District No. 3, the shops of Green street, Prince street and West Broadway; District No. 4, Wooster and Mercer streets; District 5—12th street down to Houston; District No. 6, the shops of East Houston street; District No. 7, East Side shops, mostly those of outside contractors. Owing to the numerous telephone calls on the union, the telephone company has had to install a private telephone exchange. There is also an employment bureau in the, office and there is no need for the members to walk the streets and knock at doors in search of work. The Executive Board is composed of “two delegates from each District and meets three times weekly. A meeting of shop chairmen or women-also meets every week. Such are the results of the strike of the Indies’ Shirt Waist Makers of New York. As trade unionist? we are all proud of this splendid achievement JOHN A. DYCHE, Gen. Sec. Treas.

Fall in Line, Men of Action.

By SAMUEL GOMPERS

It is an indisputable fact that on the whole the state of labor organization in this country at the present time is far better than even its friends would have ventured to prophesy immediately after the panic of October 1907. By the press and the public in general and even by many well wishers of trade unionism, the assumption was then made that for a period, to be determined by the duration of the ensuing industrial depression, labor was doomed to disheartening losses through disorganization, lowered wages, and long continued unemployment. It is true, months of idleness came to many men in certain callings, but, whatever the cause of the crisis and whether or not it was mostly a financiers’ panic only, the country has now entirely recovered from its injurious effects. But neither of the other two results feared for labor was realized to any serious extent. The local unions that were disbanded were so few in number that the average fluctuation in the total union forces year by year, was only slightly exceeded. Not one national or international union passed out of existence. As for wages, declaration was made by the American Federation of Labor, at once upon the occurrence of the panic that every possible effort would be made to oppose any attempt by employers to make the wage earners bear the cost of the depression through a reduction of their wages. This attitude of the trade unions gave pause even to the leaders of finance and great industrial enterprises. They were convinced that if they set out to cut down wage-rates they would bring upon themselves serious industrial contests, in addition to the other difficulties they were facing. In the case of the railroads in particular, the managers admitted publicly that they could not attempt to lower their wage schedules. In all its phases the policy of the American Federation of Labor in the respect just mentioned was justified by the outcome. The country has recovered from its financial set-back, and the great body of the wage-earners are to-day in a position to work for advances in their movement onward from the stage they had previously gained, instead of fighting to recover lost ground, as would have been the case had they been obliged to accept reductions in wages and extensions of the workday. A small percentage of the trade union forces lost ground; organization that had been undertaken in some directions was retarded. Recognizing these facts as true, we are enabled at the present time to look ahead and say that the prospect is most encouraging for a general advance in organization. But no outside providential force is destined to perform this work, we ourselves must carry it out. To work, then! Let every union in the American Federation of Labor, every international, national and local organization make an extraordinary effort this year to absorb in its ranks all the workers of its occupation. Let our movement to this end be concerted, cooperative and enthusiastic. We urgently request the officers of every affiliated trade union to issue a special circular to their members, informing them of the fact that all the organizations of the country have begun a strong pull, a long pull and a pull altogether for the purpose of developing our born movement, speedily, in all parts of the country, in every calling. The local unions in the various communities are invited to redouble their efforts this year in organizing all the wage-workers Within their possible reach, irrespective of craft Individual members of trade unions are asked to endeavor on all possible occasions to advance the cause of trade unionism, especially inducing the unorganized men they meet to join the union that is open to them. If each member of the union would take upon himself the obligation to bring one man into the fold of unionism, the result would be an enormous impulsive in the desired direction. Every union in the jurisdiction of the American Federation of Labor is also urged to appoint a label committee, whose duty shall be to advocate the purchase of union made products and to wait upon merchants and request them to have on sale the products of union labor bearing wherever practicable union labels. The trade union is a necessity to the modem wage-worker. By its means only can he protect himself against the aggressiveness of hostile employers and secure rates of wages and conditions of employment commensurate with the constantly growing demands of civilization. The wage workers have no other resource for common defensive purposes than the trade union. It is now generally admitted by all educated and really honest men that a thorough organization of the entire working class, to render employment and the means of subsistence less precarious, and to protect and promote the rights and liberties of the workers, by securing an equitable share of the fruits of their toil, is the most vital necessity of the present day. In the work of the organization of labor, the wisest, most energetic and devoted of us, when working individually, can not hope to be successful, but by combining our efforts ALL may succeed. At no time in the history of the labor movement has the necessity for the organization of all wage earners and the federation of their organizations been so great as at the present time. No particular locality can sustain wages much above the common level, and no particular locality can sustain wages for any length of time above the wage of another locality. To maintain high wages and a normal workday all trades and callings must be organized and federated locally as well as continentally the lack of organization among the unskilled vitally affects the organized skilled. The general organization of skilled and unskilled can only be accomplished by united action. It is the duty, as it is also the plain interest, of all working people to organize as such, meet in council and take practical steps to effect the unity of the working class, as indispensable preliminary to any I successful attempt to eliminate the evils of which we, as a class, so bitterly and justly complain. All wage workers should be union men. Their progress is limited only by those who hold aloof. Get (together, agitate, educate, and do! Don’t wait until tomorrow; tomorrow never comes. Don’t wait for someone else to start; start it yourself. Don’t hearken to the indifferent; wake them up. Don’t think it impossible, 3,000,000 organized workers prove different. It is true that single trade unions have at times been beaten in pitched battles against superior forces of limited capital, but such defeats are by no means disastrous. On the contrary, they are sometimes useful in calling the attention of the workers to the necessity of thorough organization and federation, of the inevitable obligation of bringing the yet unorganized workers into the union, of uniting the hitherto disconnected local unions into national and international unions, and of effecting a yet higher unity by the affiliation of all national and international unions in one grand federation. All of this leads to the recognition of the urgent need of extraordinary effort now by every international organization, and by every state federation, central labor union, and local trade union, through the anointment of special organization committees, or by other means [which may be deemed most advised to build up unions and more closely unite the labor movement of every locality. Let every member constitute himself a committee of one to bring. at least, one wage-earner into the union. Organize! Unite! Federate! —American Federationist.

AT THE SHIRT WAIST FACTORY. A Story—By Gertrude Barnum

It was “noon hour” at the shirt waist factory, and the “stitchers’ were scattered about, eating lunch chattering or reading. One group listened eagerly to a pale Russian girl, who was explaining a Marxian socialist tract. Another set crowded their heads together over a “dream book.” A dressy blonde sat on the steps with a huge green pickle in one hand and a yellow backed novel in the other “What are you reading. Beatrice?” asked Edna. The dressy blonde reluctantly yielded the book, and Edna opened it at the following passage: “The piteous appeal in the soft blue eyes of the helpless orphan maid touched the heart of the stern young man before her, deeply. In a flash, the cold, politic non-committal, business man was changed to an ardent, trembling lover.” “Gee! ” said Edna, “That’s a fairy tale! I wish you could get around cold, politic, non-committal business men that easy; but I’ve never seen it done. Say, Beatrice,” she added, “s’pose you come along with me to the office a minute.” A little later Beatrice found herself standing by the big oak desk of the manager of the firm, while Edna recounted to him the early morning trials of the 250 girls who daily shivered on the entrance stairs of the factory, waiting for the single “checker” to punch “time cards” and let the “operators” through the door one by one. “They keep us waiting,” she wound up, “and’ then fine us for being late. We don’t think the fines are fair.” “See here! ” said the busy manager, impatiently, “you’ll have to take your grievances to the superintendent.” Edna stood her ground firmly. “We’ve tried him for a month,” said she. “Can’t you understand, that with so many employes we have to make rules to protect ourselves?” “Yes. and you can sec it’s the same way with us. We’ve just made a rule too. Unless there’s another checker to let in the 25c girls mornings, none of us will pay tardy fines. We had to make the rule to protect ourselves. The manager looked up for the first time. “Well, well sec,” he said politely. “I can’t make any promise, but I’ll talk it over with the superintendent” The dressy Beatrice was all in a tremble when she got back to the steps and the other girls. “Goodness, Gracious, Edna!” she exclaimed. “I never dreamed you was going to put up that proposition to-day I” “You don’t do the right kind of dreaming. Here’s your pickle an’ your book; neither of ’em’s good for what ails you.” The next day Edna was radiant. “We got the extra ‘checker’ O.K. this morning,” she said, “and Beatrice has learned something. Page one, lesson one, for helpless orphan maids: ‘Stop being helpless!’ Page two, cut out appealing with soft blue eyes, and talk United States, with your tongue, fair and square.’ Page three, ‘Business men arc alright but you gotta talk business to ’em.’ ” Then, with a sigh, she added: ” I do wish you girls would stop counting on fairy tales and dream books and take up a collection of common sense among yourselves for every day use. It’s some tricks for helpless orphan maids to touch the hearts of non-committal business men. in real life.”

CLEAN ‘EM OUT.

Beans in the coffee

And dope in the milk,

Shoddy in woolens

And cotton in silk.

Sawdust in sausage

And slate in the coal.

Graft is in power.

And governs the whole.

MOTHERS WAGES.

“Mother gets up first,” said the new office boy. “She lights the fire and gets my breakfast so I can get here early. Then she gets father up, gets his breakfast, and sends him off. Then she and the baby have their breakfast.” “What is your pay here?” “1 get $.1 a week and father gels $3 a day.” “How much does your mother get?” “Mother!” he said indignantly. “Why she don’t have to work for anybody.” “Oh, I thought you just told me she worked for the whole family every morning.” “Oh, that’s for us—but there ain’t no money in that.”—Brewer’s Zeitung.

AVAILABILITY.

A nobleman was once showing a friend a rare collection of precious stones which he had gathered at a great expense and enormous amount of labor. “And yet,” he. said “they yield me no income.” His friend replied: “Come with me and I will show you two stones which cost me not 1$ each, yet they yield me a considerable income.” He took the owner of the gems to his gristmill and pointed to two gray mill stones, which were always busy grinding out grist.

DISTANTLY RELATED.

“Are you related to Barney O’Brien?” Thomas O’Brien was once asked. “Very distantly,” replied Thomas. “I was my mother’s first child—Barney was th” sivinteenth.”—Chicago Daily Socialist.

THE KITTENS AND THE MODEL by an English Sufforgette.

“On a nice chiffonier, on a bright little mat, Sat a perfectly beautiful crockery cat, So prim and so proper, So smiling and neat. And her crockery kittens were grouped at her feet. Said Fluff to her sister, “Oh look! Oh! see! That cat is a model of what we should look. If we curl our tails stiffly and sit upon mats. We may presently grow into beautiful cats! That cat never hunts, and she never climbs trees; She doesn’t chase leaves that are blown by the breeze or play with a ball or the end of a string; Oh, no I She would never attempt such a thing!! We must give up such habits and imitate her. I wonder if ’tis quite proper to purr? It is plain that no cat ought to work or to play. She should sit on a mat with her kittens all day.’ Her sister said, ‘Rubbish!’ (She was not polite. But still I consider her sentiments right.) ‘We mustn’t do nothing but simper and smirk; Our muscles and claws were intended for work! I won’t change my habits, however you fuss. For man made that model, but Nature made us!’ ”

THE “ANT AND THE FLY” Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

The fly upon the Cartwheel Thought he made all the Sound; He thought he made the Cart go on— And made the wheels go round. The Fly upon the Cartwheel Has won undying fame For Conceit that was colossal. And Ignorance the same. But today he has a Rival As we roll down History’s Track— For the “Anti” on the Cartwheel Thinks she makes the Wheels go back!

“Why do people have silver weddings, pa?” “Just to show to the world what their powers of endurance have been.”—Judge.

THE GENERAL EXECUTIVE BOARD will hold their next meeting on Sunday, May 8, at Beethoven Hall, New York, at 19 a. m. Locals having special request to make shall communicate before that date. JOHN A. DYCHE. Gen. Secy. Treas.

DEMOCRACY IN THE TRADE UNION.

Every person in a Trade Union should be put upon some Committee for practical work. Only in this way can the organization use all of its strength. As it is, generally, three or four officers and the business agent arc overworked, and the rest of the members of the union sit by, without responsibility at the meetings and let off steam, either by fault-finding orations or by sullen silence, relieved by an occasional complaint that the meeting lasts so long. A Committee on Absentees, for example, might be made up of a member or two from each shop, and have for its object devising of ways and means for interesting and holding indifferent members. In their reports they should give the reasons which keep members from attending meetings, and suggest remedies A Committee to form Auxiliary Label Committees among various classes and nationalities should be very active in finding out what retail stores are likely to handle the label and then organize consumers in the neighborhoods of such stores to create a large demand for label articles. A Committee on Entertainment should arrange for balls and parties and fairs, etc. A Visiting Committee should visit sick members and those in trouble to let them feel the solidarity of the union feeling. A Clerical Committee should help the Secretary with clerical work. An Educational Committee should arrange for classes, lectures, etc. A General Trade Committee should keep informed of conditions, in each trade, throughout the country, and report at meetings any important matters, concerning any branch of the trade, in any city or town in the country—particularly any news which will throw light upon successful methods of building up trade conditions. A Grievance Committee should sift out the important from unimportant grievances and present the former, only, etc., etc., etc. One might go on indefinitely suggesting committees which could contribute to strengthening the union, in various ways. “But,” some may object, “If all these committees were to report at each meeting, we never get home!” The answer to that objection is simple. At present, too often what is called a “meeting” is given over to hours of petty wrangling over unimportant matters, “hot air” from a few who monopolize the floor because they have ” a gift of gab” or “an axe to grind”‘ or “a grievance to unload.” A good chairman could see that each person who takes the floor should speak briefly and to the point, representing the mature conclusions of a committee, and not speaking more than once without special permission. A Democratic chairman recognizes the great educational valine of giving every member of a union some training in speaking in meeting, and speaking briefly and to the point. It is of utmost importance that all members be trained to take responsibility—not only in voting intelligently for the right officers, and measures which will help; but also in the power of expressing themselves property at a meeting, in few well-chosen words. This method of training a union to work by committees, makes a great difference in the interest members take in attending meetings where a committee has some plan at heart. All the members of that committee are likely to be present at meetings, to carry out that plan. Very often some quiet man or girl, who has always before seemed a mere cipher will suddenly wake up, if given responsibility, and develop into a very active and useful committee member. The old fashioned way of expecting three or four officers to “run’ a union and devoting meetings to “kicking” because those few officers do not accomplish everything alone and unaided in a day, is giving place to the new unionism, where members are made to realize that a chain is no stronger than its weakest link and that every member of an organization is to blame for any of its faults which are allowed to continue. GERTRUDE PARNUM.

AGAINST UNIONS.

Forcing men to pay dues in labor unions against their will is a conspiracy and therefore unlawful according to a decision handed down last week by the appellate court. The case was that of twenty employees of the Chicago Railway company against the officers and members of the North and West Side Street Car Men’s Union. The complainants resigned from the union on Feb. 1, 1908 and refused thereafter to pay dues. The union voted to strike unless the company forced the men back into the union or discharged them from the service. The “insurgents”‘ applied for an injunction to restrain the union from striking and the company from discharging them or forcing them to rejoin the union. Judge Walker refused to issue the injunction and the case was appealed.

THE BOOT AND SHOE WORKERS UNION.

John F. Tobin. President R. and S. W. U.

The beginning of the Boot and Shoe Workers Union was in 1803 when a number of small organizations in the shoe trade amalgamated on a due rate of roe. per week with 2c. per capita per week to support the National and no sick or death benefits. The dues were too low to provide funds with which to promote the growth of the union and in 1806 another convention was called at Rochester, N.Y., where the present constitution was framed. This constitution providing for 25c. per week dues, two-thirds per week to be forwarded to the National Union and a sick benefit of $5.00 per week payable for 13 weeks beginning after the first week of sickness, and an insurance feature of $5.00 for 6 months membership and $106 for two years membership, has proven an unqualified success. With some care taken in guarding the funds against illegimate claims, the 16 2-3C. per week, which is the National’s share has been sufficient to pay all claims, including S4.00 per week strike pay and leave a respectable balance in the treasury at all times. Strikes are not financed by tin union unless reviewed by the General Board, when strike sanction may be granted with benefits. The chief tactic of construction in the Boot and Shoe Workers Union is the promotion of the Union Stamp, the label of the organization Requisite to the use of the Union Stamp by manufacturers is the closed shop agreement calling for the employment of members exclusively, requiring the firm to submit all matters of change pertaining to wages or labor conditions to the union for consideration with arbitration as the final decider of all questions, the same course to be followed on matters emanating from the union. The right to hire and discharge if tacitly given to the employer although the Union retains the privilege of inquiring into causes of discharges. The policy of the union is included for the most part in striving to secure control over non-union concerns regardless of prices or conditions of labor obtaining. In fact, the lower the price paid for labor the more the union feels elated in securing the closed shop power over the firm to begin to correct the evils existing and gradually raise prices to a competitive level. Another important part in the policy of the Hoot and Shoe Workers Union is its effort to keep the price paid for labor in union factories within a scope which will allow the union manufacturers to sell shoes in the market in competition with non-union concerns. It pursues a course which aims to bring up prices for labor and at the same time not penalize firms who are willing to do business with the union and run closed shops. To bring this about is quite difficult but is being clone quite successfully through the extensive advertising of the Union Stamp, through labor papers, leather trade journals, billboards and direct representatives of the union popularizing its stamp before the public by means of lecture? associated with entertaining in theatres and large auditoriums and visits to union meetings. ‘This has a tendency to increase the volume of business for firms using the stamp and gives them considerable advantage in a business way over their non-union competitors, thus enabling them to meet the exactions of the union for increased prices. Strikes are entered into very infrequently as the most of the members are bound by the Union Stamp arbitration contract and all matters which are not mutually adjusted between the union and manufacturer must be arbitrated. Provided any member strikes in violation of the Union Stamp agreement the National Union fulfills its obligations under the contract and proceeds to assist the firm to fill ‘heir places. The union’s reputation of maintaining its contracts, at any cost, its steadfast course of recognizing both -‘des of the labor situation, and demanding strict observance by the members of the laws of the organization, has assisted greatly in the progress it has made.

THE NEW UNION OF CARUTHERS.

This article should lie read and reread by every trade unionist. The rapidity with which our villages frequently grow into flourishing, populous cities and industrial centers is one of the wonders of our American enterprise. Where a generation ago was a straggling village of a thousand> or fifteen hundred inhabitants may now exist a city of 20,000, composed principally those dependent for employment on the factories and workshops that have grown up with the city, or, rather, have caused the city to grow, the products of which may reach the furthermost ends of the earth. Such a city was Caruthers, in one of the middle western states. Fourteen years before this story opens Caruthers had a population of less than 2,000. Now it has 18,000, a mayor and city council, street railways, and electric lights and power — all that goes to make up a bustling industrial city. John Strong had gone to Caruthers when it was a village, with little more capital than his two hands and his skill as a machinist, from an eastern city, where he had, while still young, grown tired of working for a wage that scarcely more than provided him the strength from day to day to continue at work. From his little beginning in Caruthers had grown a great manufacturing establishment, which helped the city to grow as the city helped it to grow, and his workmen now numbered almost a hundred. There had been few, if any, labor organizations in Caruthers, and, as a necessary attendant, wages were low as compared with the great cities, though, of course, the cost of living was less. But with the growth of the city the latter advanced, as is usual, and wages, too, had slowly advanced—slower than living expenses, as is also usual. Finally, the organizer appeared, and it, was but a little time until a committee’ waited on Mr. Strong, as president of the Caruthers Manufacturing Company, and he was informed that his workmen had enrolled themselves as members of “I am very glad to hear it, gentlemen,” said Mr. Strong, smilingly. ” I was a union man from the day when I completed my apprenticeship until I established this Business, and I am a firm believer in trade unionism.” “Then,” said the spokesman of the committee, “I am sure we will be able to get along amicably.” “I have no doubt of it,” said Mr. Strong, “especially if you prove yourselves true union men in all that the term means. There has been great progress in trade unionism in the last few years.” “Very great, indeed, sir,” said the spokesman. “Yes,” said Mr. Strong, “and I have tried to keep abreast of the movement by reading trade union literature. It may surprise you to know that I am a subscribe for a number of labor publications.” “Well, that is rather unusual for employers, I am afraid,” said the committee chairman. “It is gratifying to meet so liberal-minded an employer as we find you, Mr. Strong. We do not contemplate any violent changes in. the wage scale now, nor perhaps soon, and we do not anticipate any great opposition from you if we shall claim a reasonable increase,” “I hope you will always find me reasonable.” said Mr. Strong, “and if your members prove union men to the core—for I hold that the employer has as much to gain from unionism as the employed; that each owes a duty to the other—I am sure our relations will always be pleasant. Perhaps I may go further than you. do in my belief in unionism and all that it entails and may have some criticisms to offer later.” Within a few weeks the union presented a scale of prices to the president of the company, making some slight advances in wages, which he signed, after inspecting it carefully. “Gentlemen.” he said to the committee, “I have signed your scale cheerfully, for it is quite reasonable; but I do it with the reservation that if I find the members are not true to the principles of unionism, as to which I will conduct an investigation, I am free to withdraw from it.” “We are willing to abide by that, sir,” said the president of the union, who was chairman of the committee. “If at any time you land that we are not keeping to the true principles of unionism, we will be glad to have you point it out to us and to rectify our error or absolve you from your agreement.” Within six months the organizers had formed unions in all the principle occupations, and although all proprietors had not proved as tractable and reasonable as Mr. Strong, and there had been a few strikes and lockouts, at the end of that time the town was pretty thoroughly organized into unions. Everything had gone along peaceably and quietly in the Caruthers Manufacturing Company’s great establishment. Every member of the mechanical force was in the union. A few—there are always some black sheep—had demurred to joining, but were at once given to understand that they had no sympathy from the company in their resistance and they speedily surrendered. It was with some surprise that the president of the union received a message from Mr. Strong that he would like to see him, but he went at once— this some months after organization. “You will remember the verbal clause that I added to our agreement when I signed the scale of prices,” said Mr. Strong, “and that I might claim to be released from it under certain circumstances.” “Very well indeed, sir,” said the president, “but I am at a loss to know how we have given offense.” “I should like to have permission to’ address your union at its next meeting.” said Mr. Strong, “at which I will show you that you have not kept faith with me and are not true to the principles of unionism. Your committee asked me to point out wherein you might be lacking, and I want to do it in the presence of the entire union, so that the members will not get a second hand. I am very much in earnest in this matter. If I am to live up to the principles of unionism the members must do so, too,” “We will be very glad to have you address the meeting,” said President Phelps, “and I will cause such notice to be sent out that every member will be there, I am totally in the dark as to our shortcoming. hut the union will hear you with pleasure.” The news that Mr. Strong had something to say to the union brought every member out, and after the routine business was transacted he was invited in from the ante-room, where he had been waiting. ‘”Gentlemen.” said President Phelps, “you are all aware that Mr. Strong has stated his desire to address our union. I have no need to introduce him. You all know him, and such has been his interest in our movement that I believe he knows every one of you. We will now hear him.” “Mr. President and gentlemen of the union,” began Mr. Strong, “I will not tire you with long introductory words. I was gratified when you formed your union, for I am a believer in trade unions. I was a member of a union before many of you ever saw the inside of a -workshop. When you presented your scale of wages to me, as the president of the company, I cheerfully signed it. But I signed it with the announced reservation that I would not feel hound by it unless you Comported yourselves as true union men. You have not done so.” A sensational buzz ran around the room. / “Among the requirements of your union is one that we shall not employ any but union men. ‘Is it not so?” “Yes, yes!” came from all parts of the room. “You refuse to handle material that comes from non-union shops. Am I right?” “Yes, Yes! again came from the assembled men. “You will neither work with nonunion men nor use the product of non union men in working for the company.” “No, no! ” “Mr. President, will you step here a moment?” Mr. Phelps wonderingly walked to the open space in which Mr. Strong stood. “Mr. President, said Mr. Strong, as he turned back Mr. Phelps’ coat and examined the inside pocket, “I do not find the union label. Was that suit of clothes made by a union tailor?” Mr. Phelps reddened and returned to his seat. “Mr. Secretary, that is a handsome pair of shoes you have, but, looking closely, they have no union label.” The Secretary’s feet were hastily taken down from the top of the desk, where their position had added much to his comfort. *While waiting in the anteroom I examined many of the hats that I saw hanging there, and though I found a few with union labels, I feel sure they are there without the owners’ knowledge. Who among you has a hat with the union label in it? ” A young man rose. ” I think my hat has the union label.” he said. “You think!” The sarcasm in. Mr. Strong’s voice caused the hopeful young man to seat himself suddenly. Most of you use tobacco in some form,” continued the speaker. “I did as a workman and do as an employer, and so am not here to condemn the practice. Which of you can show me a piece of union-made tobacco? Who of you smoke blue-label cigars?” Guessing was too hazardous. Nobody rose. “I have looked into the matter of the stores patronized by most of you, and I have found no indication that any of you ever asked for union-made goods of any kind. Is it not so?” There were able debaters in the union, but none rose to combat him. “Some of the bakeries in this city are union and some are not. Have you supported your fellow unionists and withheld support from the non-unionists? You have not!” The general uneasiness was distinctly noticeable. “Gentlemen, I have given you a fair trial. You are unionists only so far as your own wages and conditions are concerned. I might go into this a good deal further, for I have thoroughly investigated it; but I have shown enough to convince any fair-minded man that you are not union men. You don’t know the meaning of the term!” One might have knocked the whole assemblage over with a feather. “You demand that we shall employ union labor while you spend your union wages for the product of scabs. You will not work with a scab, but you buy what he produces on equal terms with union goods. You will not work with scab-made material, but you will wear it and cat it and smoke it. You require the employer to boycott^ non-union labor while you encourage it. I must not employ a scab, but I must compete with his employer for your trade. You demand union conditions in the way of comfortable and sanitary shops, and you support the sweat-shop and tenement house producers. And you call yourselves union men! Pah! I am ashamed of you! I am disgusted with you I repudiate you and your scale of wages!” Mr. Strong abruptly ended his speech and started for the door. The silence of the meeting was almost awful. It was a room full of dead men so far as they showed any signs of life. He had nearly reached the door, when he stopped as though a new thought had occurred to him. He turned around and faced the meeting. “Mr. President,” he said—the anger was gone from his voice. “Mr. President, perhaps I have been too harsh. I should have taken into consideration that most of you arc new unionists and have as yet little conception of what unionism means. The whole theory and scope of trade unionism is not to be grasped in six short months. You have yet to learn that it has its obligations as well as its benefits. We are all more or less afflicted with the human instinct to buy where we can the cheapest, regardless of the fact that it may be the dearest in the end. I am going to give you another probation before I become your enemy. Perhaps you have not reasoned that in demanding patronage you must concede patronage. It may not have occurred to you that the workingmen arc the principal buyers of nearly all products, and that in buying of the non-union employer you are putting the union employer at a disadvantage. Theoretically yon consider the interests of all unionists identical, but you set your theory at naught by your practice. I will wait another six months to see if you are union men.”

THE RECENT STRIKE OF SHIRT WAIST MAKERS IN PHILADELPHIA.

By Ida Mayerson

It was on December 20th of last year that about four thousand girls engaged in the shirt waist industry in the City of Philadelphia walked out from their shops with the cry that they would rather starve outside the shops than inside. The shirt waist industry in Philadelphia is a comparatively new one only about fourteen or fifteen years old; but in that short time the employers have been busy doing two things, firstly in cutting down the prices every year, and secondly, as a result of the timidity of the toiling girls, in amassing capital. It was s a bitter winter in Philadelphia when the strike began. Yet, the poor half-starved, girls held on heroically for seven long weeks, until a partially successful settlement was brought about the courage of the girls cannot be too highly praised. First they appealed to those who remained behind in the shops to join them; but when peaceful persuasion and remonstrance failed, they were seized with righteous indignation and prompted no doubt by dire necessity, hastily used less dignified means. Think of these frail and delicate girls defying the club of the police and the assaults of their opponents! Since business is not conducted on philanthropic principles, it can be imagined that very little consideration was shown them. The strike came on just before Christmas, and the police expecting to be thanked for their services to the employers gave them sufficient ‘assistance and protection. Their conduct was such as to convince every impartial observer that the zeal they displayed in arresting right a n d left anyone who approached the vicinity of the factory, was not of a platonic nature. They went so far as to arrest casual passers by. a n d one of these latter happened to be a prominent society lady No less than 46 0 arrests were made during the strike. The cheer that burst forth from the members of the union was the only answer Mr. Strong needed to convince him that his lesson had not fallen on barren minds. Within the specified time union signs all over druthers showed that the true meaning of unionism had been learned, not alone by the employees of the Caruthers Manufacturing Company, who constituted the greater number of the union of their trade, but by all the trade unionists and their sympathizers.”—American Federation Sl. However, ft is now five weeks after the strike, and what”, you might ask. has it accomplished for t h e girls, both morally and financially? Well, it is regrettable that after so stubborn and courageous fight only a partial success was s won. Our demands were truly just. We asked for higher wages. The average wage of the shirtwaist gift before the strike was s six, or six and a half dollars a week, and this in a metropolitan city like Philadelphia is barely enough to keep body and soul together. Then we asked for shorter r hours. Ought not this, properly speaking to be the business of the community? Is it not generally admitted that if the woman is injured society must suffer? Do no one ever stop to think what it means for a girl to grind for ten or eleven hours a day amid the dirt and dust of sweatshop, or factory, reduced entirely to a sort of human machine, although she is a human being throbbing with the aspirations, ambitions and hopes of life? As a result of the seven weeks’ fight the working hours have been brought down to 52 hours per week, or about five hours less than formerly. We also demanded improved sanitary conditions, which is rather the duty of the community to see to, and as a result of the strike some necessary improvements have been made. With regard to the demand for the recognition of the union, the concession wrung from the employers amounts to this, that in the event of any grievances arising the employee’s complain to the union representative who submits the matter to the union for consideration and adjustment. If there were no union of waist makers in Philadelphia prices would have been reduced; as it is we gained a decided increase. These improvements alone show that the strike was necessary; but we also gained both moral and financial advantages, though it’s ultimate effects are only slowly being recognized by the rank and file. Few people realize that a strike is really never lost, even if declared so by its opponents; for if no actual increase is affected, at least the stability of the old wage is assured, otherwise prices may be continually lowered. The strike is dreaded by the employer, because he often loses a great deal more than his employees. The energy that is wasted on both sides is really deplorable, but how else are we to overcome the obstinacy of the employers in refusing to grant proper conditions of labor, owing to the practical result referred to, a large number of girl have been enrolled as member? The union and our numerical strength in Philadelphia is much greater than before. We have now proper head start which will be used for educational purposes. These contain library and reading room, and we have also established evening classes where the English language, American history and economics are taught. Arrangements are now being made for introducing Sunday social evenings to which all members of the union are welcome; also a dancing class for those who desire to spend their time in such manner. All this will promote healthful recreation and mutual improvement to relieve the grinding monotony, caused by the clatter of the machines all day long. The girls are becoming enthusiastic about all this progress made, and we are looking forward to a better future. There are men—even in the ranks of organized Labor—who believe that the movement is one of self-interest, and that its only object is to gain some monetary benefit for the members of Unions. If this were so the Labor Movement would be only an incident—and a passing one—in the scheme of Industrial development. As it is, the Labor Movement is part and parcel of Human Evolution without which mankind would stagnate, progress be suspended, and the end of things not very far off. —New Zealand Worker. Badge worn by the Philadelphia Waist Makers during their last General Strike.

There is no excuse for you wearing a Non-Union Waist Sig. Klein of 50 Third Ave N.Y. City, sells Union Labels Waist.